Stellar Parenting: Giant Star Clusters Make New Stars by 'Adopting' Stray Cosmic Gases

Among the most striking objects in the universe are the dense, glittering swarms of stars known as globular clusters. Astronomers had long thought globular clusters formed their millions of stars in bulk at around the same time, with each cluster's stars having very similar ages, much like twin brothers and sisters. Yet the recent discoveries of young stars within old globular clusters have scrambled this tidy picture.

Instead of having all their stellar progeny at once, globular clusters can somehow bear second or even third sets of thousands of sibling stars. Now a new study led by researchers at the National Astronomical Observatories, Chinese Academy of Sciences (NAOC) and the Kavli Institute for Astronomy and Astrophysics (KIAA) at Peking University, might explain these puzzling, successive stellar generations.

Using observations by the Hubble Space Telescope, the research team has for the first time found young populations of stars within globular clusters that have apparently developed courtesy of star-forming gas flowing in from outside of the clusters themselves. This method stands in contrast to the conventional idea of the clusters' initial stars shedding gas as they age in order to spark future rounds of star birth.

The study is published today in the journal Nature.

Globular clusters are spherical, densely packed groups of stars orbiting the outskirts of galaxies. Our home galaxy, the Milky Way, hosts several hundred. Most of these local, massive clusters are quite old, however, so the NAOC and KIAA research team turned their attention to young and intermediate-aged clusters found in two nearby dwarf galaxies, collectively called the Magellanic Clouds.

Specifically, the researchers used Hubble observations of the globular clusters NGC 1783 and NGC 1696 in the Large Magellanic Cloud, along with NGC 411 in the Small Magellanic Cloud. "This study offers new insight on the problem of multiple stellar populations in star clusters," said Dr. Chengyuan Li, the first author of the paper.

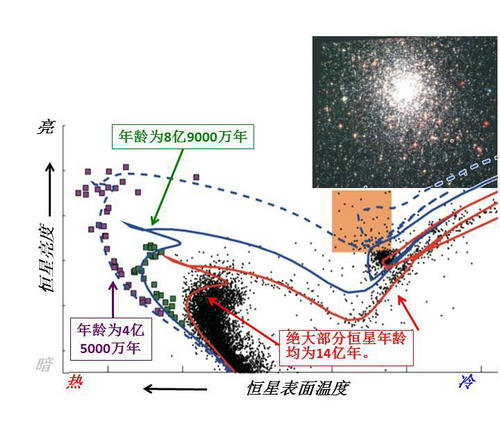

Scientists routinely infer the ages of stars by looking at their colors and brightnesses. Within NGC 1783, for example, the research team identified an initial population of stars aged 1.4 billion years, along with two newer populations that formed 890 million and 450 million years ago.

“What is the most straightforward explanation for these unexpectedly differing stellar ages? Some globular clusters might retain enough gas and dust to crank out multiple generations of stars, but this seems unlikely,” said Licai Deng of NAOC and Li’s Ph.D. supervisor. "Our explanation that secondary stellar populations originate from gas accreted from the clusters' environments is the strongest alternative idea put forward to date," said Richard de Grijs, an astronomer at KIAA and co-supervisor of Chengyuan Li.

In a manner of speaking, globular clusters appear capable of "adopting" baby stars — or at least the material with which to form new stars—rather than creating more "biological" children as parents in a human family might choose to do.

"The most massive stars that form in a globular cluster only live about 10 million years before exploding as supernovae, which blow away the remaining gassy, dusty fuel required for making new stars," Deng said. "Our study suggests the gaseous fuel for these new stellar populations has an origin that is external to the cluster, rather than internal," said Chengyuan Li.

The research team proposes that globular clusters can sweep up stray gas and dust they encounter while moving about their respective host galaxies. The theory of newborn stars arising in clusters as they "adopt" interstellar gases actually dates back to a 1952 paper. More than a half-century later, this once speculative idea suddenly has key evidence to support it. Future studies will aim to extend the findings to other Magellanic Cloud as well as Milky Way globular clusters.

The work also includes researchers from the Northwestern University, USA.

The research is funded, in part, by the National Natural Science Foundation of China.

A portrait of the massive globular cluster NGC 1783 in the Large Magellanic Cloud. A new study suggests the globular cluster swept up stray gas and dust from outside the cluster to give birth to three different generations of stars. (Credit: ESA/Hubble & NASA. Acknowledgement: Judy Schmidt (geckzilla.com))

Observational data reveals the characteristics of variously aged stars observed in the globular cluster NGC 1783. Black points indicate stars 1.4 billion years and older, while green squares show the 890 million year old stars, and the purple squares along with the black points represented in the orange square to the right signify 450 million year old stars. The globular cluster clearly has three substantial populations of stars with different ages. (Credit: Chengyuan Li and Richard de Grijs, KIAA)

The members of Chinese research team include Richard de Grijs (KIAA), Yu Xin, Yi Hu, Chengyuan Li (PMO), Licai Deng (from left to right in the picture).